During the 2025 field season, I had the opportunity to assist with bat acoustic monitoring at The Nature Conservancy’s Surry Mountain Preserve located in southwestern New Hampshire. Acoustic monitoring was conducted across multiple sites in Surry to assess bat activity and species presence. This work builds on previous years’ data and aligns with NH Fish and Game guidance and USFWS-approved programs for bat acoustic analysis. New Hampshire has 8 species of bats which includes the Eastern red bat, Silver-haired bat, Northern long-eared bat (federally threatened and state endangered), Tricolored bat (state endangered), Hoary bat, Eastern small-footed bat (state endangered), Little brown bat (state endangered), and the Big brown bat. All species are of conservation concern but our highest priority is on determining if any of the state endangered or federally threatened species are present at the site. Based on my previous experience with bat acoustic detection, I chose to take on the monitoring and figuring out the analysis process as my independent project during my AmeriCorps term.

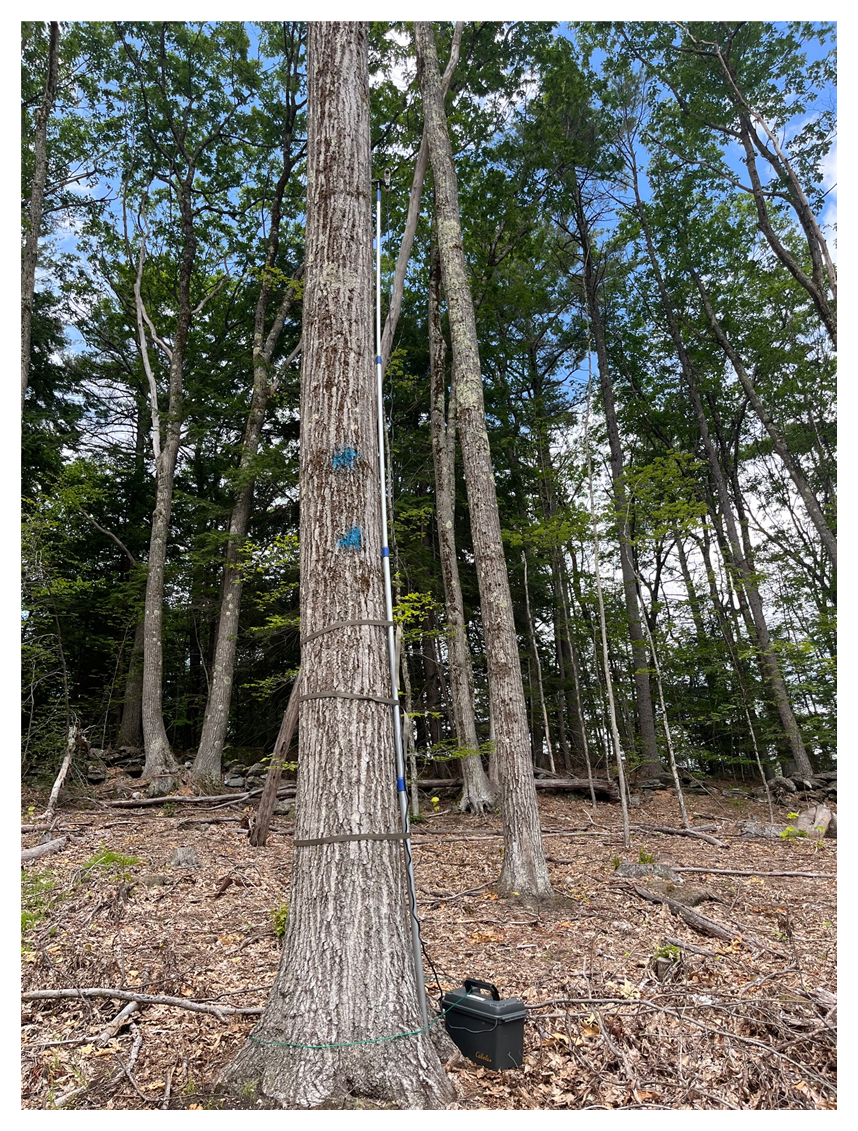

In order to record bat activity, a detection device is connected to external batteries and an ultrasonic microphone attached to a large pole. Bats prefer to move through the forest in openings, so these microphones are placed in forest gaps and along edges of open areas to create the best chance of detection. The devices record continuously for about seven nights during peak resident activity between early July and mid-August. I was able to collect 7 to 15 nights of recordings from each site this year putting our total at almost 200 GB of acoustic files. During the recording process the sound files are clipped into 3 second segments since bat calls are extremely fast which means there were thousands of files collected. All these files needed to be individually processed which began my search of finding the right analysis program and learning as much as I could about the process. I connected with several bat researchers from around the state and individuals from multiple universities to decide the best method to get results and how to conduct future research in the field. I started the initial process of examining files and was able to confirm that so far we’ve detected at least 5 of the 8 bat species in NH.

In my initial search for acoustic information, I was able to connect with a professor from SNHU who expressed interest in creating an opportunity for some of her students to assist with the time-consuming process of identifying bat calls in all of the files. Once my AmeriCorps term is over, students will continue the process of manually identifying specific bat calls from numerous files that the analysis system was not able to clearly identify on its own. They’ll be using our data to create a presentation for their Undergraduate Research Day this spring as well as presenting their results to NH Fish and Game. By creating this connection, we hope to continue to have new groups of university students assist with the data analysis process each year as more research is conducted. Not only did I have the opportunity to learn a lot on my own through this process, but I’m happy to see that through this service project I’ve helped to engage students in the community and introduce them to current conservation practices.

Mackenzie is serving with The Nature Conservancy as a member of their Stewardship team. She’s originally from New Jersey and has a degree in Wildlife Ecology and minor in Forestry from the University of Florida. Her favorite part about living in New Hampshire so far has been getting to see all of the coastal birds starting to migrate back to the Lubberland Creek Preserve. Learn more about Mackenzie here.